The Shelter

The Shelter

"The rumour was that HIV patients died in hospitals,

because the government was poisoning them"

In the fight against HIV/AIDS in Myanmar, politics is never far away. The founders of a shelter for HIV-infected patients, members of opposition party National League for Democracy (NLD), have been treating a constant flow of patients for over a decade. “They accused us of being communists, because we used the Red Ribbon.”

Ma Cho Cho Myat knew she was sick. Her legs hurt. She felt weak. Her hair was falling out. The hospital told her it was something called AIDS, but she didn’t know what that meant until her parents expelled her from their home and forbade her from seeing her own daughter. Suddenly the strange disease was the only thing she had left.

Ma Cho Cho Myat, 44, told her story in the dormitory of the National League for Democracy’s HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care Centre in Yangon’s outer South Dagon Township, where she has lived off and on for two years. She was resting with a cold as she spoke, but usually helps out in the kitchen or washes clothes for the centre’s other residents. The shelter provides her with counselling and a place to stay while she receives treatment elsewhere in the city.

It is a comfort for Ma Cho Cho Myat to be among others who share her plight: people marked with death in the eyes of their friends and families, who dare not seek help in their hometowns; even if they knew what to look for, even if they could find it.

“For those who succumb

to the disease,

the shelter arranges their funerals.”

The centre has been accepting those who are HIV positive, such as Ma Cho Cho Myat, since it opened in 2002. The National League for Democracy opened a similar centre nearby a few years later and the two facilities are accommodating about 180 people, including 30 children. Individuals, and sometimes whole families infected with HIV, the human-immunodeficiency virus, come from throughout Myanmar to receive treatment. The centre provides them with shelter, food, transportation and medicine. “It is not supposed to be long term,” said shelter director Ko Yaza, “but we never send anyone away.” Some have called the shelter home for years. For those who succumb to the disease, the shelter arranges their funerals. Maung Aung Paing Soe, 14, who lost his parents to the virus, moved in permanently after growing too old to stay at a nearby orphanage.

A badge of death

The estimated number of people living with HIV in Myanmar hovers between 170.000 and 220.000, but an untold number have not been diagnosed. Many of those who have been diagnosed do their best to hide it. “People didn’t want to go to the government-run Waibargi Infectious Diseases hospital,” said Ko Yaza. “The rumour was that patients died there because the government wanted to get rid of them and was poisoning them.”

That kind of hearsay was common when NLD activist Daw Phyu Phyu Thin and a handful of volunteers began welcoming patients, at first at a party office and then in the shelter, built on land owned by her family in 2002. In those days, the government effort to combat HIV/AIDS was beginning and was constrained by a limited health budget and an anaemic healthcare system. But far more toxic was the decades of pent-up fear and superstition about AIDS.

“Hospices provided by monasteries or shelters like the one run by the NLD were one of the few place were HIV patients had access to treatment at that time,” says Eamonn Murphy, UNAIDS country director in Myanmar. “Patients were being forced out of their homes, from their families and their communities as a result of stigma and ignorance. Obviously, people hid their HIV status, and still do, until late in the infection. Which is when you’re so sick you can’t really hide it.”

“A woman might be shunned as a whore, a man a drug addict; and even

children with HIV are often treated as

dangerous health risks.”

Access to treatment for those with HIV/AIDS has improved dramatically in recent years. The government is allocating more funding to health and rebuilding the healthcare system. An increasing number of domestic and foreign organisations are providing treatment and care. But the stigma of infection still clings like a cancer to the HIV community. A woman might be shunned as a whore, a man a fornicator or drug addict; even children born with the virus are often treated as dangerous health risks.

The government has officially condemned the prejudice, but in the absence of anti-discrimination laws, it persists. Mr Murphy showed me a menu from a Yangon restaurant that featured colourful images of dishes such as squid and prawn curries – and proclaimed that the food was free of hepatitis and HIV.

“What do you think that means?” he said. “It means they’re testing their staff. Can you get HIV from food handlers? No, and it’s not the law to test food handlers. But if you’re working somewhere and someone finds out you have HIV, you’ll lose your job probably. That’s the kind of thing we’re dealing with.”

Ko Yaza claims that in its early years the shelter experienced harassment from officials because of its link to the NLD. The officials exploited ignorance about HIV/AIDS and used it as a weapon. “Many would come from far away to live near the shelter and officials would harass their landlords and spread false rumours,” Ko Yaza said. “The officials would say that the patients were a dire health hazard and that the virus could be spread by mosquitoes and even by floodwaters.” Hospitals would turn away patients who sought admission while accompanied by NLD members. Ko Yaza and nine other shelter staff were once arrested on a range of charges and were accused of being communists because shelter’s documents featured the red ribbon, the international symbol of support and compassion for those with HIV/AIDs. When a visit in 2010 by NLD leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi drew attention to the shelter, the centre’s permit was revoked and the clinic came close to being shut down.

A report on the harassment in leading publication The Irrawaddy said township authorities later apologised and claimed they were acting on orders from high-ranking officials. Ko Yaza is convinced the former military regime regarded HIV/AIDS as a national embarrassment and conspired to stifle projects that focused attention on the disease. When organisations involved in tackling HIV/AIDS began compiling estimates of the number of infected people, the government negotiated down the figure “as if it were a price,” he said.

The politics of AIDS

Mr Murphy doesn’t agree with Ko Yaza’s narrative. The UNAIDS country manager suspects that antagonism towards the shelter was spawned at the grassroots level and not from the government. Mr Murphy: “When the shelter was opened, the government even cooperated with Nobel Peace Prize laureate Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and foreign organisations to establish the Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar, the country’s first major source of funding to combat the disease. No matter what the government did, it was not enough and was criticised, often for political reasons. Think about positive reinforcement: the more you get criticised for something, the less you want to work on it. It becomes something you don’t want to talk about. It stigmatises the issue from a different angle.”

The seeds planted during the military regime are beginning to bloom as the government increases spending on health. Although more work is needed to fight discrimination and stigma, access to treatment has soared in recent years as a result of increased public and donor resources, and the activities of NGOs such as Doctors Without Borders Holland, which treats about 30,000 HIV/AIDS patients throughout the country.

Yet the separation of politics and public health isn’t a simple matter for shelter director Daw Phyu Phyu Thin, who won a seat in parliament for the NLD in the 2012 by-elections in Yangon’s Mingala Taungnyunt Township. In its early years, the shelter accepted any patient regardless of political affiliation, as well as soldiers and public servants. “We were determined to retain the reference to the NLD in the name of the shelter, despite harassment, because the facility was a symbol of hope and change as well as providing an essential service. We couldn’t take away the NLD name. It made us strong.”

She believes corruption and a dysfunctional bureaucracy continue to pose the greatest challenges to the national effort against HIV/AIDS. On paper, hospitals have adequate stocks of antiretroviral (ARV) drugs and other crucial medicines, but distributing them has been slow and inefficient. “There is so much medicine. But one day the Wairbargi hospital only gave 50 people medicine while as many people were still waiting.”

This is one reason why many of those with HIV/AIDS rely on services provided by foreign NGO’s and shelters such as the one run by the NLD rather than the government’s health care system. Official figures show that in 2013, the Health Ministry spent about US$22 million on the campaign against HIV/AIDS. The next year the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria spent $141 million on the campaign. Mr Murphy regards the government’s partnerships with NGOs and organisations such as the Global Fund as a mark of progress. For Daw Phyu Phyu Thin however, it shows the ineptitude of the current government.

“I do not deny that Myanmar’s political system has work to do,” the UNAIDS director said, “but the battle against HIV has no place for old grudges and cheap shots in parliament. Tackling HIV is about embracing things as they are, good and bad, with a shared goal of making life better for people with HIV. That’s what we all should focus on.”

One day at a time

In the future, Myanmar could be a place where facilities such as the shelters run by the NLD are no longer needed. The provision of treatment and care for those with HIV/AIDS is becoming more decentralised as clinics open outside urban areas. Hopefully, as more people with HIV receive the treatment they need to settle back into ordinary life, the stigma will begin to ebb. There may come a time when no one with HIV/AIDS has to travel far from their homes to find treatment, and are not afraid to do so.

In the meantime, the NLD’s shelters are admitting a constant flow of patients. The two facilities accepted a total of 147 patients in July 2015 alone, and are finding it harder to meet the cost of care. The NLD is taking on more projects and party resources are growing scarce. Daw Phyu Phyu Thin said the NLD will always stand by people with HIV, referring to a pledge made by party leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi when she visited the shelter in 2010. But each month the shelters rely a little more on private donors, mostly ordinary people who give what they can, often to earn religious merit. Perhaps a few thousand kyat (a few dollars), or a box of instant noodles for the kitchen.

The patients help where they can, sharing their food, medicine and money with each other, helping the volunteers with their work or caring for small children when their parents are sick. Cooperation between staff and patients is one reason why the centres continue to operate. Ko Yaza is optimistic about the future. The shelter was recently given a large plot of land. He displayed an image of a big, modern building. It will replace both centres when it is built. In the meantime, they still won’t turn anyone away.

Ma Hnin Si (27)

"I Used To Be Afraid Of HIV Patients Myself"

“I am from Kalay, Sagaing Region, close to the Indian border. My parents both died and I lost touch with my three brothers who still live in my hometown. I worked as a singer in a restaurant in Yangon. When I started losing weight and lost my appetite, my neighbour told me I should get myself tested. By that time I already had bad skin problems. I weighed only 32 kilograms. I was diagnosed with HIV/AIDS two months ago. I think I contracted the disease at the restaurant where I worked. Sometimes I had to go with customers, because I had no money.

I live full-time in the shelter now, but I am still waiting for medical treatment. I will probably receive antiretroviral drugs when the doctor visits again. Of course I am afraid to die, but the only thing I can do is to prepare myself mentally for the treatment and survive.

When I gain weight again and my health improves, I hope to rent a room somewhere and find a job. If I don’t take care of myself, who will? For the moment I have no money, but I have a strong mind. Before I knew I was sick, I was afraid of HIV/AIDS patients. I had to change my mindset, but I have realised that people treat me differently now. Most people still have strong prejudices about HIV/AIDS patients. My biggest desire is that I will someday have a partner and a family. I just hope it is my destiny.”

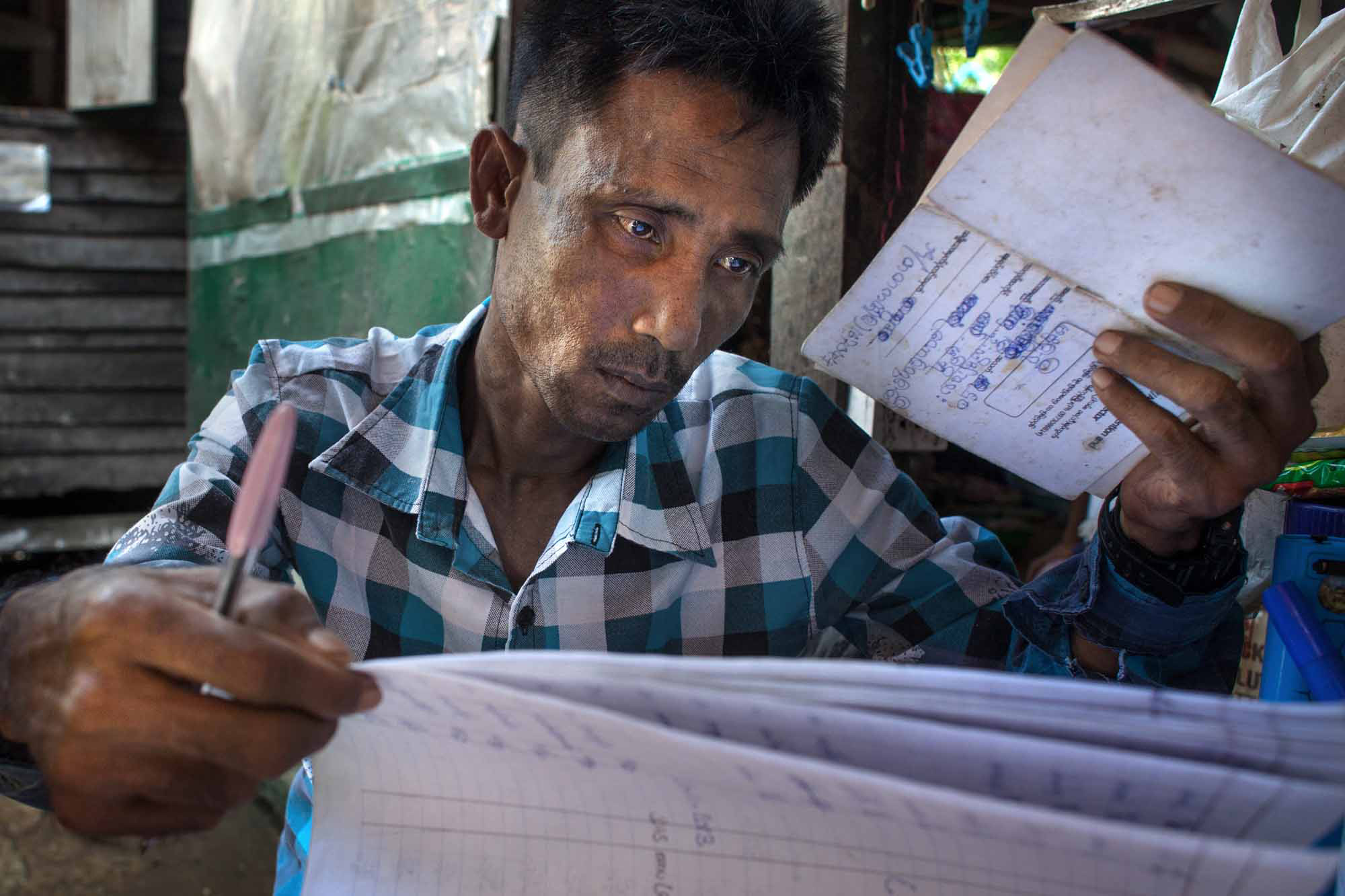

Ko Myint San (48)

"It’s up to the Buddha"

“I was born and raised in Bogalay, 150 kilometres from Yangon. I manage a group of twenty girls there who knit nets for fishing boats. Bogalay is in the midst of the Irrawaddy delta where Cyclone Nargis struck in May 2008.

The storm surge surprised us completely. Before we knew it, the water was everywhere. The current was strong, but luckily I managed to grab hold of a tree. I managed to avoid being swept away by taking off my longyi and looping it around the trunk. After six hours, the water level dropped, and I could finally let go. Out of our family of sixteen, only three survived.

When I suddenly started to lose weight, I decided that I should take an HIV test. I tested positive. My first reaction? I felt really bad and I was scared. I was embarrassed too, was afraid to go home. I feared that people would discriminate against me. In undeveloped areas, villagers don’t know anything about HIV/AIDS. The government does not educate the people.

When I was younger, I did some bad things. I am single now, but back then I slept around with girls. That is probably how I contracted the disease. Now, at the shelter, I am receiving antiretroviral treatment. The medicines made me dizzy at first, but it is better now.

I’ve survived two disasters, so I’m not worried. It is up to the Buddha. I have made a lot of merit in my life. I donate regularly, and I take care of my paralysed younger brother. I am not stressed. I just have to take care of my health as good I can. In a couple of weeks I hope to go back home, back to my job. I will tell my employees about my disease, but I want to educate others as well. No, I am not scared to tell the girls that work for me. I am their leader. It is also important that I go back to my village, because I donated 600 US dollars for the building of a religious centre. That building is my baby. They cannot perform the Buddhist rituals to open it without me there.”

Htet Tun Oo (43)

"My boss reacted surprisingly well"

“I am a truck driver from Pathein in the Irrawaddy delta, some 200 kilometres from Yangon. My wife found out she was HIV-positive before I did, about a year ago. After her diagnosis, I took a test and as it turned out, I was positive as well. I contracted the disease from my wife. Her former husband died of AIDS.

Some of my friends have died of AIDS too, so I have seen what they went through. At first, I was afraid to die, but as I read more about the disease, I learned that it could be treated. I am a National League for Democracy member, and that’s how I came to know about Phyu Phyu Thin’s shelter here in Yangon. If my wife and I had chosen to be treated in a rural clinic, I am sure that she would have died soon after her diagnosis. The drugs she is getting are helping. She is already gaining weight.

I am pretty sure now that I will survive too. I am optimistic, because the antiretroviral drugs seem to work for me too. The side effects are not too bad: dizziness and some kidney problems. My only fear is that I will accidentally be given the wrong medicine.

The HIV/AIDS stigma is strong in Myanmar. In my town, people know that my wife is HIV-positive, so our friends stay away. The Government and the Ministry of Health should do more to create awareness about HIV/AIDS and how you can contract it. People should know that you don’t get it by just being around a person who is infected.

Luckily not everybody is so ignorant. When I told my employer about my disease I was afraid that he would fire me, but he reacted surprisingly well. He said: ‘Work as much as you can handle’. So when I return to Pathein, I will take up the same job again.”